While researching Electrodyne I came across a seminar

that Lynn Fuston (www.3daudioinc.com)

had hosted, “Mic Pres In Paradise.” One of the members on

the panel was an engineer I had never heard of named John Hall.

It turned out John was one of the designers of the discrete op amp

used in the early Electrodyne modules. As John tells it,

“The 709 was an IC designed by BOB Wiler at Fairchild and used in

the original Electrodyne 709 module. We redesigned it as a

discrete monolithic op amp [with much better performance specs]

and that’s what we used in the early Electrodyne 709 (line amp

module), 710, 711 and 712 mic/line/EQ modules. Same with the

earlier designed Quad-Eights which were basically Electrodyne

consoles that were re-branded..”

I was curious to know how the Quad-Eight connection had come

about. Hall continues, “Bud Bennett was a salesman and

started a company called Quad-Eight, so named because he invented

a process for Technicolor Corporation.” Elaborating on this

process a bit more, former Quad-Eight manufacturing engineer David

M. Gordon told me “the process that was called ‘Quad-Eight’ was to

print four strips of 8 mm film on one piece of specially

perforated 35 mm film stock which would then be slit after

developing. This enabled the lab to utilize the 35 mm

processing equipment to develop consumer 8 mm film, hence

‘Quad-Eight.’” “Bud would take orders for film consoles and order

a console from Electrodyne,” said Hall. “He’s have it

shipped to his place in North Hollywood. At which point he

would have the same engraver that we used put a ‘Q’ over the ‘E’

of our Electrodyne console and hence a Quad-Eight console was

born.”

I asked Hall if at some point they started building consoles

themselves and the designs were basically exact replicas of what

Electrodyne had designed for them? “Yes, in fact they

stole all our designs! I used to work on Sundays a lot and

I went in there this one Sunday and worked all day, everything

was fine. The next day I come back to work and all our

schematics were out all over the place, on the floor with foot

prints on them and everything and all our blueprint toner ink

was gone. Well, sure enough Bud paid the truck driver for

Electrodyne at the time and had come in and copied all our

designs. All except the A-1000 op amp design, as we never

did a schematic for just that reason!”

Talking to John about the background of Electrodyne I

realized there was a bit of audio history here that has never

covered before in print. John put me in touch with a

gentleman named Don King, the former service manager and sales

man for Electrodyne and Langevin, who agreed to fill in some of

the missing details.

Don sent me a fine, detailed audio cassette, and as it’s opening

said, “Virginia, there were two Electrodynes. Both Electrodynes were founded by progenitors

of the motion picture industry. For the sound requirements

of the motion picture industry at that time required you to not

only capture dialogue in a sound stage, yet sometimes that stage

was moving, reminiscent of the old Wells Fargo Stage where you had

not only actors, but hoses, the stage coach itself, environment

issues and the dialogue.

Electrodynes. Both Electrodynes were founded by progenitors

of the motion picture industry. For the sound requirements

of the motion picture industry at that time required you to not

only capture dialogue in a sound stage, yet sometimes that stage

was moving, reminiscent of the old Wells Fargo Stage where you had

not only actors, but hoses, the stage coach itself, environment

issues and the dialogue. |

“The first Electrodyne

components were based on tubes. Not like the tubes we

have today; these were very small with the wires hanging right out

of the bottom. These were not socketed tubes as they are

today. And they were very powerful, with over 100 dB of

preamp gain to fulfill these sound requirements. Eventually

Art Davis sold Cinema to Aerovox, Inc., who really didn’t know

what they were doing in that particular field and eventually

closed down the original Electrodyne company.”

King went on to share with me that year later, Art Moser,

who had retainer the name “Electrodyne,” agreed to sell Don

McLaughlin (a friend of his) the name “Electrodyne” and the

second incarnation of Electrodyne was born. “This time,

however, they did not use the tube-based design but the new

integrated circuit [IC op amp] designs that were just coming

out about that time.” Actually theirs was an improved

Fairchild 709 integrated circuit redesigned and called the

A1000. Later this would morph into the Electrodyne

A2000.

C ontinuing

the op amp lineage for a moment, David M. Gordon told

me, “The first Quad-Eight op amp would be called the AM3 (the

square, potted Block that looks like an API 2520). Chief

engineer for Quad-Eight, Deane Jensen, would later redesign this

into the AM4 hybrid op amp [which he later refined into the

famous Jensen 990 op amp] and after Jensen left Quad-Eight this

would morph into the AM10 [found in the Coronado, Pacifica and

Ventura consoles], finally after Mitsubishi acquired Quad-Eight,

it would become the AM12 [and later AM12b -their attempt at a

cost reduced replacement for the AM10].” ontinuing

the op amp lineage for a moment, David M. Gordon told

me, “The first Quad-Eight op amp would be called the AM3 (the

square, potted Block that looks like an API 2520). Chief

engineer for Quad-Eight, Deane Jensen, would later redesign this

into the AM4 hybrid op amp [which he later refined into the

famous Jensen 990 op amp] and after Jensen left Quad-Eight this

would morph into the AM10 [found in the Coronado, Pacifica and

Ventura consoles], finally after Mitsubishi acquired Quad-Eight,

it would become the AM12 [and later AM12b -their attempt at a

cost reduced replacement for the AM10].”

King continues, “Electrodyne’s true claim to fame was that it

was the first company to take all these separate components -the

mic preamplifier, the line amplifier, controller, equalizer,

router and attenuator -and combine them all into one, as they

called it, ‘input module.’” Today we know this as a console

channel strip. “Not only did they combine all these

electronics, they also made it so that it was not impedance

critical. You see, until Electrodyne developed this method

you had to match all your different ohm-ages when combining

different pieces of electronics. Broadcast consoles were

especially very impedance critical. Electrodyne eliminated

the need for this by developing the ‘active combining network’

(acting as a bridged amplifier), which was a 10,000-ohm device

used to ‘route’ all the individual 600 ohm ‘integrated circuits’

modules’” (read channel strips), thus developing what we now

know as the ‘recording bus.’ Your could add or subtract

many, many 600 ohm modules to this system before it became a

problem.” Something we don’t’ even have to think about

today, thanks to Electrodyne.

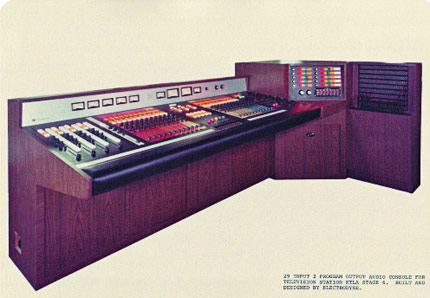

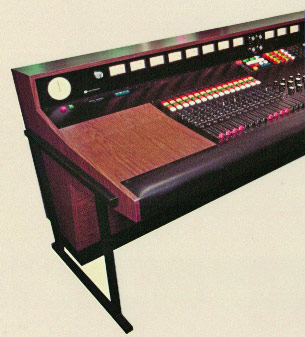

The

consoles were manufactured in-house at their new state of the

art facility built in North Hollywood, California, which at the

time had its own research and development department, sheet

metal fabrication shop, carpentry shop (the early Electrodyne

console housings were made of wood) and floor assembly area.

All of this was a very new concept at the time, and the world of

console manufacturing as we know it would never be the same. The

consoles were manufactured in-house at their new state of the

art facility built in North Hollywood, California, which at the

time had its own research and development department, sheet

metal fabrication shop, carpentry shop (the early Electrodyne

console housings were made of wood) and floor assembly area.

All of this was a very new concept at the time, and the world of

console manufacturing as we know it would never be the same.

Unique to these consoles, they could be ordered in what was

advertised at the time as “another Electrodyne first . . . A

Kaleidoscope Of Color” as the engraved console surface over the

aluminum was Formica. This led to the wild colors that can

be found on the strips today. Even though you could order

just about any color, I was told by one of the original

designers that they had to talk Emmylou Harris (and then

husband/producer) Brian Ahern out of the shocking pink color

they wanted. It was a little “too much.”

The companies born out of Electrodyne read like a

who’s who in the annals of the audio industry.

Ed Reichenbach was hired to build the audio transformers used

in the consoles. Don McLaughlin would later fund Ed to

become his own transformer company,

Reichenbach Engineering (“a truly superior device”, states

King). Gene Sakasgowa went on to start Sake Magnetics from

the Gauss Corporation, who were part of MCA Technologies Group,

the same company that would eventually acquire Electrodyne

around 1970. Langevin was bought by Electrodyne because

Altec and Gliss couldn’t supply slide wire attenuators fast

enough to Electrodyne. “And therefore Altec couldn’t even

build their own consoles at the time,” asserts King, so by

buying Langevin they were sure to have sufficient supplies on

hand. Later the Computer Equipment Company would purchase

MCA Technologies (around 1972) and a new company would be formed

which had most of these companies under their corporate parent

company, now called Cetec. King went on to say, “The Ce

taken from Computer Equipment Company, the tec taken from MCA

TECnologies.” Thus, you had Electrodyne, Langevin, Saki,

Gauss, Optimation and Reichenbach all under the same parent

company. Keeping in mind all the original designs came

from the first motion picture companies Western Electric and RCA

and you can see how the lineage of the audio industry was born.

King would go to state, “Don McLaughlin would later retain

most of Electrodyne’s designs but would form a new company

calle

David M. Gordon elaborates further, “Deane Jensen, who would

go on to chief engineer for Quad-Eight, started his own op amp

designs before starting to sell Reichenbach

transformers as

retrofit units for most big name consoles and then he went full

time with his own company:

Jensen Transformers by Reichenbach Engineering.”

d Sphere, which is still alive and well today but now

manufacturing audio consoles anymore.” I called Don

McLaughlin to ask him about the similarities of the original

Electrodyne consoles and the Sphere console. McLaughlin

explained, “The Sphere preamp and EQ were actually an

improvement to the ones used in the Electrodyne consoles.

The original equalizer inductors would saturate when pushed all

way and start ringing. Sphere used bigger inductors to

stop this and added more frequency points, switchable frequency

points.” The graphic version of this EQ would go to be

called the Sphere 900 Series EQ (there was a 900 and, later, 910

and 920 versions that could be ordered). I had heard of

these EQs and seen pictures of them but never got to use any of

them. “A shame,” McLaughlin muses. “Several

mastering houses at the time used these as their equalizers.

There was also a fixed frequency semi parametric EQ as well as a

fully parametric EQ (the EQ 1014) that could be ordered along

with those graphics, however the customer wanted it configured.”

When asked how the mic pres differed from the Electrodynes,

McLaughlin sates “the mic pres were basically an improved John

Hall design using a new op amp Hall designed called the SPA 62.

Reichenbach still supplied the transformer.” In his quest

for sonic perfection McLaughlin told me, “Later I also came up

with a different circuit design that would stop the phase switch

from popping when engaged, same with the EQ in/out switch.”

This is a retrofit that McLaughlin still does to existing Sphere

consoles today.

The list of Sphere purchasers, as expected, is quite

impressive. Artists such as Ronny Milsap, Hank

Snow, The Judds and major studios of the time, such as Sigma

Sound and Alpha Audio, bought Sphere consoles. As

McLaughlin told me, more than a dozen Sphere consoles ended up

in Nashville in the long run. Even the U.S. White House

bought one in 1975 under the Ford Administration.

Unfortunately, this was sold last year, replaced by a new

digital console. Something tells me that the board won’t

last the 30 years the Sphere did - time will tell.

Langevin, through the help of Don King, was later bought by

Manley Labs. Gauss is still alive as Gauss International

(making high speed tape duplicators). Reichenbach

Engineering ceased operations about four years ago and all the

assets were purchased by his son Tom Reichenbach of

CineMag Engineering, who can still make all the old

Quad-Eight and Electrodyne transformers. Quite a history

that lives on even in today’s world of hi-tech recording.

In The End

David M. Gordon was the last manufacturing manager of

Quad-Eight in Valencia, California until it closed. As

David tells it, in brief . . . “In the ‘70s Quad-Eight made a

deal to acquire Westrex (it fit well with the focus on ths film

business). QE/W was the result, then Mitsubishi purchased

the company as an American presence (Mitsubishi Pro Audio) to

sell the digital multitrack that they built, bundled with a

console (Westar). When Mitsubishi decided that they could

not sustain the company they sold it to Electori Co. It

was run as Quad-Eight electronics until Mr. Hatori’s death when

it was closed down.” David now works as managing director

for Josephson Engineering Inc. (

www.josephson.com ), makers of some of today’s finest

microphones.

Even today Quad-Eight lives on, to a certain degree.

Ken Hirsch started Orphan Audio out of a love for these old

vintage designs (

www.orphanaudio.com ). You can actually but “kits”

from Orphan Audio to build your own Quad-Eight mic pres from

vintage line amp cards. For the savvy studio engineer this

could be a way to have the vintage sound without the guesswork

or research required when converting these line cards from

scratch. And for anyone who owns a Quad-Eight console, Ken

may have just the parts you need to keep it running as smooth,

plus there’s a Quad-Eight

http://www.josephson.com),/forum on his site.

Recently A-Designs Audio (

www.adesignsaudio.com ) introduced the familiarly named

Pacifica mic preamp (see review this issue) with a design based

on (yet different) than the vintage Quad-Eight preamps.

Today there are several studios that pride themselves on

owning one of these vintage beauties from this past -my studio,

Silvertone, being one of them- with a 1969 Electrodyne ACC1204

(15x4) console. Not only do they sound great, they look

cool as hell and afer thirty plus years in service are still

considered by some as one the best sounding consoles designed.

Yes, when an old pot finally goes or a cap leaks and dries out

they’re a pain in the ass to get fixed, but what you are

rewarded with in sound more than makes up for keeping these

running smoothly. As my tech, Ken McKim (Retrospec,

Trouble Report owner, Allaire Studio’s technician), tells me,

“The beauty of these modules is in the simplicity of their

design.” Just try to buy the same build today and see what

you spend for it.

As with a lot of the manufacturers of the past I don’t think

they realized at the time what a profound effect their creations

would have on the world of art well into the next century.

Listen to the soncis of Pink Floyd’s The Wall (mixed on

three Quad-Eights tied together) or Boston’s “More Than A

Feeling” and hear the history of Electrodyne, Quad-Eight and

Sphere.

I would like to thank the following people for their

direct contributions to this article:

John Hall, Don King, Don McLaughlin, David M. Gordon,

Ken McKim, Pat Morford, Bob Ohlsson, Mark Addison, Danny

McKinney, Scott Benson, Tony Perrrino, Carl Landa, Jeff Britton

and Frank Moscowitz. I would also like to invite any

individuals who can fill in the blanks to please write

TapeOp magazine so that together we canput together the most

accurate and detailed account of our audio lineage.

Orphan Audio is reestablishing the Quad_Eight name.

The MP-227 preamp and classic channel strip products show

shipping.

www.quadeightelectronics.com

Visit Mark Addison’s fantastic Quad-Eight Forum

www.quadeight.net

Author: Larry DeVivo runs Silvertone Mastering in New

York State.

www.silvertonemastering.com

|